If supermarkets are the villain, why do local producers supply them?

Why one Somerset producer is comfortable with selling into supermarkets – and why one is not

Within the strange and curious world of supermarkets, where £10-million-a-year CEOs1 assure the public their business is not profiteering, tweely-named farms are invented to distract from the industrial nature of their operations, slave labour occasionally rears its head, and – in former years – binned food was doused in bleach to deter the hungry, you’d be tempted to think that all is not honest and altruistic.

Indignancies also tend to be felt if you’re a producer. One of the stats this newsletter has aired a couple times before is that, for every British pound sterling a person spends in a supermarket, the producer commonly receives about 8 pence. More recent studies however, such as the one by food charity Sustain, will tell you it’s even less than that.

As is often the case (but, as this newsletter has pointed out before, not always the case), supermarkets can’t be beat on price or convenience. Their sheer control of the market (at least 85% of all food is sold through them), and efforts in providing the best price for the consumer, is creating superficial ideals of how much food should cost, amounting to a system rarely fair on others but themselves.

Ask your average producer in Somerset, and they’d likely tell you they’re not party to this system, as they don’t or can’t make enough to fulfil a typical supermarket’s quantity of orders. But there’s also a good chance they’d rather not anyway.

“Personally, I will always do everything I can to avoid supplying them,” Oliver Dowding tells the WFJ. In 2016, Oliver and partner Jane co-founded Dowding’s, a cider and apple juice maker in Wincanton using fruit from either surplus stock or their organic orchard. “Even if it were to be only a couple of local stores, and even if it were one of the more ‘ethical’ options, such as Waitrose.”

Oliver is part of an estimated 56% of UK farmers who, instead of or in addition to supermarkets, want to supply customers via food hubs, independent stores, and farmers’ markets. Partly because it allows them more direct interactions with a local audience, partly because it reduces their carbon footprint, but critically because they get a price more commensurate with the true cost of producing food. “For many people supplying supermarkets,” says Oliver, “the margins are incredibly thin. One other ‘real’ cider producer – as opposed to those producing watered-down imitation ciders – makes a margin of about 3p per bottle when supplying Tesco. I’m unclear as to why he does it.”

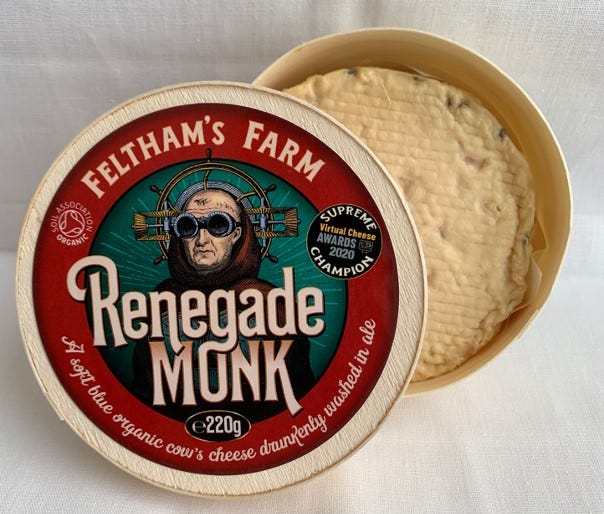

Perhaps another Somerset producer will give us some idea. Another like, say, Feltham’s Farm, not too far down the road from Oliver in Templecombe. Run by Penny Nagle and Marcus Ferguson, Feltham’s sell their Rebel Nun and Gert Lush organic cheeses into Waitrose, but also supply small independent shops around the UK, direct online or at farmers’ markets, and via various cheesemongers.

Not at some of the cheesemongers you might expect, though. A surprise to me, but Neal’s Yard Dairy – possibly the biggest independent cheesemonger in the UK – has something of a prejudice against cheese from pasteurised milk. It says on their website: “All of Britain’s territorial cheeses were once raw milk cheeses [...] Pasteurisation, refrigeration and homogenisation are all methods of standardising milk. Heavily processed milk does not make interesting cheese. That is why Neal’s Yard Dairy seeks out cheese made from raw, single farm milk.”

As you might have guessed by now, Feltham’s Farm cheese is pasteurised. Mostly, and as much as Marcus and Penny “love raw milk cheese”, Penny tells the WFJ that, given they are relatively new cheesemakers making non-traditional soft cheese, “the current environmental health climate is more suited to hard cheeses [which are less susceptible to E. coli and Listeria] than soft,” and that “having an E. coli scare from raw milk can destroy a small cheese company – and really inhibit even quite a large established one.”

In addition to that, soft cheeses are obviously much more perishable than harder varieties, which Penny thinks generally makes stocking a tad more “risky” for delis and cheesemongers.

All this amounts to a situation wherein Feltham’s Farm is fairly limited in where it can sell its products. Which is why, in November 2011, they took up Waitrose’s offer to stock their ale-washed and slightly blue Rebel Nun. “Of all the supermarkets, Waitrose has always demonstrated a commitment to organic in general, and they pay a fair price,” says Penny. “They have never tried to negotiate us down in price, and are reasonable people to work with, having been massively supportive when we had burst water pipes at Christmas in 2022.”2

Presumably not wanting to endanger their contract with Waitrose, Penny is not as forthcoming about whether she thinks the price she receives is as fair as it is in other forms of retail. But we can make an educated guess – given Rebel Nun currently sells into Waitrose at £7.60, but online and via farmers’ markets (where there are comparatively very few if any middle men to compensate3) at a minimum of £9, it’s safe to assume what price point Feltham’s has more control over, and considers more equitable.

Still, that may be beside the point – of the more general benefits producers have in stocking supermarkets, simply having your product on a shelf browsed by hundreds if not thousands of customers a day is often perceived as invaluable, irrespective of whether your products actually sell or not. It may be a primary motivator, or a welcome side effect, but Feltham’s cheeses – even the Rebel Monk and La Fresca Margarita designated as “exclusive” to indie cheesemongers – have certainly become more recognised since they appeared in Waitrose outlets.

There was a time when, if you were an interesting and well-meaning producer peddling your wares via a supermarket, I’d have assumed you’d sold your soul to beelzebub, and were complicit in the same profit-driven industrialised food chain you wanted to dismantle or surpass. The reality is, as in all other things, not quite so absolute. Supermarkets might still be the behemoth standing in the way of a fairer food system for people and planet, but at least it’s now not so difficult to comprehend that, depending on their circumstance, some of our favourite local producers mightn’t exist without them.

Read next>

Notes on a food shop in Frome [WFJ #71]

In this week’s WFJ, I point out such revelations as: Why food is often cheaper in independent shops; the ludicrous affordability of items in Denude; and that supermarkets are, in many cases, conning you out of your money. If that kind of thing interests you, and you’re not already subscribed, you can do so for the monthly fee of £3.50. Feel free to unsub straight after – I won’t judge.

Tesco CEO Ken Murphy: £9.9m earnings, Sainsbury’s chief exec Simon Roberts: £4.9m, M&S Food CEO Stuart Machin: £4.7m

It might not be saying too much, but Waitrose do seem to be the most sympathetic towards producers. At the other end of the scale, and consistent with the footnote above, is Tesco. Oliver says: “If one were able to negotiate better prices with Tesco then you would be eligible for negotiator of the year awards. They are ruthless and not people I ever want to have to deal with.”

Once again invoking the worlds of Oliver Dowding, producers “can only supply the multiple retailers through third parties. Therefore another chunk out of our end price would be gobbled up.”

![Notes on a food shop in Frome [WFJ #71]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!EdvQ!,w_280,h_280,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fd3ee391d-4460-4dc0-95d7-2a1fafb4a374_4032x3024.jpeg)