Who grew your clothes? [WFJ #83]

Fashion, like food before it, is starting to reforge our connection with the land. The South West's role in this movement can't be understated

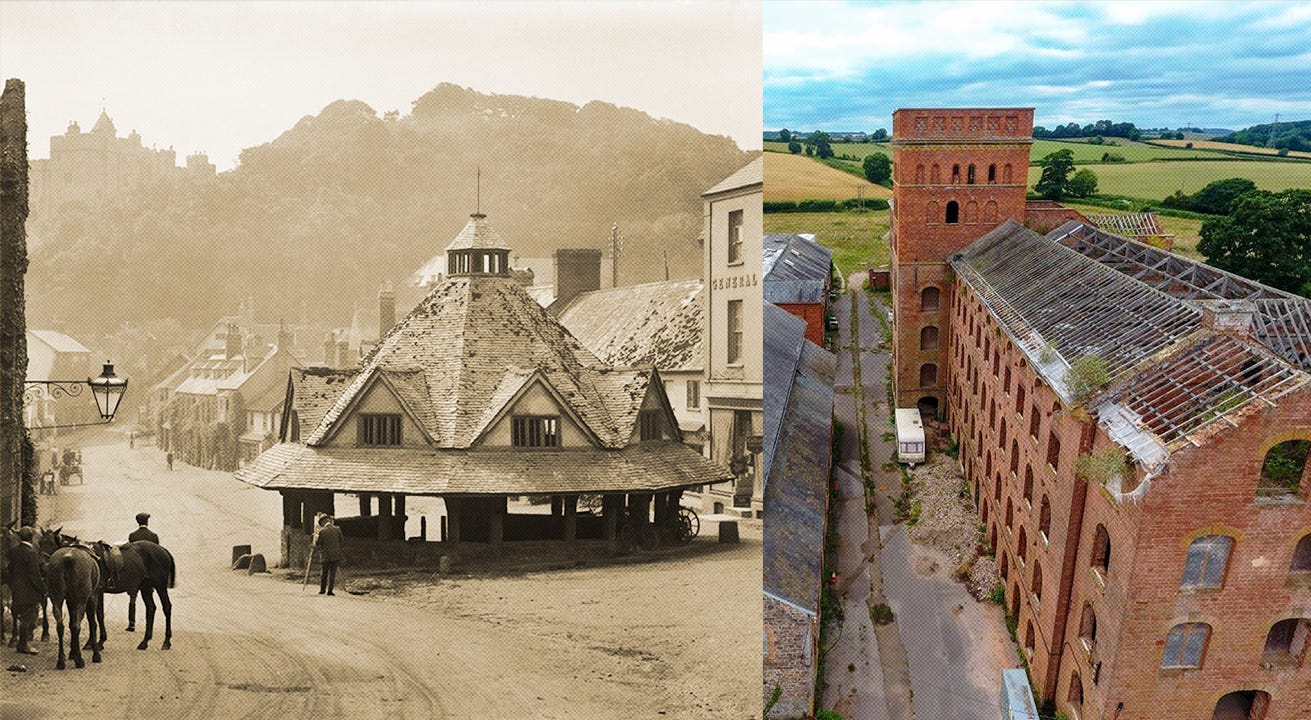

You wouldn’t know it at first glance, but Somerset – and the wider South West – played, for centuries, a huge role in the textile trade. Squint at some of the buildings in Somerset, including many of the protected ones in Frome, Wellington, Shepton Mallet, and Taunton, and whether they resemble old spinning mills or weaving factories, evidence isn’t too hard to make out.

While these industries have become almost non-existent, the connection between the area’s fertile pastures for animal-rearing, and the shirt on your back, has not been entirely neglected. Actually, you might say, it's witnessing a resurgence.

Much like food before it – and partly because of the global supply chain crises of recent years – people are starting to ask questions about where their clothes come from, how they’re made, and who makes them. Without going too deep into other parallels with food1 (e.g. fast food and fast fashion) a movement called Fibreshed is uniting the constituent parts which make up a more localised, circular, and sustainable textile economy.

This deserves a bit more clarification: Where Fibreshed is a global thing, it’s generally not characterised as such – there exists a few dozen local ‘Fibresheds’ around the world, each relevant to their bioregion of what they produce and the skills reliant on them. There’s seven Fibresheds the UK currently, and the South West’s is probably the country’s most established.

“The thing about the Fibreshed model,” South West England Fibreshed founder Emma Hague tells the WFJ, “and where it's got the biggest potential to disrupt, is that it's asking our local landscapes to dictate really what it is that we wear.”

In the case of Somerset, and the South West at large, that means the hemp and flax growers, as well as the processors turning that raw material into linen. But, since the region’s climate and soils are generally better suited to livestock, the South West’s Fibreshed is mostly comprised of wool and hide producers, as well as the weavers, dyers, felters, spinners, tanners, designers, and tailors they are dependent on.

Since synthetic fibres and cheaper variations have entered the market, both wool and hide have been massively undervalued, treated as little more than a byproduct of the meat and dairy industry. Some farms in the region with agroecological principles at heart, like Fernhill Farm in the Mendips, and Heritage Graziers in the Cotswolds, want to prove they’re worth much more than that.

“Several people, including a couple of our members, have illuminated how opaque the leather supply chain is,” Emma says. “And how few tanneries we have left in the UK, and also how few of them are prepared to keep the provenance associated with the hides that go through processing.”

The bigger challenge is in helping or enabling farmers access to the means to add value, which in many cases starts with giving them the confidence to speak to those in the fashion industry, and visa versa. This, again, is where Fibreshed comes in. “There's a desire to reconnect,” Emma says, “but also a fear around how to, because the two worlds have become so disconnected and foreign to one another.”

The results of these connections and collaborations are out there to see (and wear), in the eventual product – Bristol Cloth being one such example. But also channelled within the stories of the people involved. At The Frome Independent market this Sunday (1st October), South West England Fibreshed will pop up with a stall out front of the library. There'll be spinner and knitwear designer Marina Skua processing fleece into yarn; Katy Warriner showing how to saddle stitch belt leather; and Jade Ogden of The Handloom Room demonstrating handweaving on a traditional table loom. There’ll also be, as Emma says, “several other members who have a lot to say about what they do and a lot of passion for both their craft and the Fibershed movement,” while all materials will originate from the South West landscape.

With South West England Fibreshed’s appearance at The Frome Independent occurring in conjunction with Sustainable Fashion Week (25th Sept - 8th Oct), it’s particularly good timing. It’ll also, hopefully, serve as an introduction to the idea that reconnecting with the land can occur as much through what you wear as what you eat. Where more sustainable attitudes towards food, such as in agroecological or nature-friendly approaches, don’t necessarily seek to bring in wholesale changes across the food system at large, similar is true here.

“We're not trying to replace conventional fashion,” Emma says. “And nor do we want to create a system which produces things in such high volumes that there's absurd amounts of waste. We realise the need to create a whole new paradigm for thinking about the production and consumption of fashion, which is about meeting demand, but also doing it in a way that works with nature. To me, it just seems the simplest way of doing that is working with nature's own low-input processes.”

Speaking of the parallels between food and fibre, one of my pitching students recently had published this charming piece on a cake traditionally shared among Welsh sheep farmers during shearing time.