Somerset's ice cream counterculture

Generally speaking, to buy an ice cream is to buy into industrial, ultra-processed food. Here in dairy country however, small-scale producers are scooping up something more worthwhile

When the sun appears, so too does Britain’s affection for ice cream.

Well, that’s not entirely true – the UK consumes more ice cream in the colder months, per capita, than any other country. But still, on a bright warm day, business tends to rocket, with almost 90% of ice cream sales occurring between April and September.

In Somerset, that means independent ice cream makers like Brickell’s, Palette & Pasture, Styles, and Yeo Valley are more apparent. Depending on how you look at it though, the general state of the ice cream industry is far from sunny at the moment. One company – that being Unilever – has an almost complete hold on UK ice cream, controlling the biggest brands in the market such as Magnum, Cornetto, Ben & Jerry’s, and Carte d’Or.

Let’s just say Unilever’s record across a variety of its practices isn’t exactly glowing. It scores “very badly” in Ethical Consumer’s ‘animals’ rating, while its so-called commitments towards other considerate farming methods have ranged from vague (“growing more grass,” they say), to uninspiring if not disturbing (e.g. the “innovative cow feeds” that will supposedly, if not controversially, help reduce methane emissions).

It may sound cynical, but Big Dairy would rather you were kept in the dark anyway. Estimates suggest that as much as 20% of the UK’s total dairy herd are either ‘zero-grazed’ or have very limited access to pasture. James Rebanks, as part of his commentary on modern farming in English Pastoral, claims this number is more like 50% (though I’m not sure where he got that number from), while the BBC says in the region of one million cattle are kept in battery units in the UK, making them more reliant on imported feed and routine use of antibiotics.

Either way, megafarms are becoming more common in the UK. If more people were aware of that, there’d be a backlash not unlike what was recently levelled at dairy companies using the controversial feed additive Bovaer. Of course, Big Dairy knows the perils of bad press, which is why brands – as Muller and Arla have done – will show you adverts depicting cows grazing green open pastures when in fact they’re often shoulder-to-shoulder in an intensive unit.

Somerset dweller, brand strategist, and author Matt Buttrick is not unfamiliar to these kinds of portrayals, having worked with some of the big players in the dairy industry. He writes in his new book Moreish: The Hidden Secrets of What We Eat and Why that Cathedral City’s branding is meant to reassure consumers with signals of “strength, safety and pastoral care," while Dairylea, Laughing Cow, and Babybel “portray a childlike innocence and the natural purity of an idyllic countryside.”

But on visiting brands like Dairy Crest creamery in Cornwall, sometimes the realities are grey, sterile, and at no small scale. “The word ‘creamery’ conjures up a certain bucolic romance,” Matt tells the WFJ. “The aircraft hangar-sized manufacturing plant coming over the horizon a little less so.”

I scream, we scream, for something different

Farming systems supplying Big Dairy favours housing cattle indoors for the sake of efficiency and yield. Smaller dairies, however, will want them outside as much as the weather will allow, while even fewer will grow a pasture of deep rooting species-rich plants on which to feed their cows, ultimately minimising soil disturbance, providing a better diet for their herd, and producing more flavourful ice cream.

This is what the likes of Brickell’s and Yeo Valley have made a point of doing. Westcombe herdsman Nick Millard, who helps supply Brickell’s with all their milk, says the dairy has given up maize (commonly grown to feed cattle over winter), and is significantly reducing its reliance on other conventional fodder crops in favour of greener, more leafy plants. “The nature of the grazing pastures and silage lands means [the cows] are filled with not just grasses but also flowery legumes and herbs that are rich in tannins and odour-active compounds called terpenes, which make for a beautifully perfumed and richer flavoured milk.” Nick also says the reduction in cereals (barley and wheat another common animal fodder) has helped the milk take on a creamier finish.

Part of this transition has also necessitated the reintroduction of native breeds. In Brickell’s case, the shorthorn. Though a smaller (and therefore lower-yielding) cow, it is also lighter, putting less strain on the land, and content to stand out in less clement weather, unlike your typical Holstein Fresian, which Brickell’s co-founder Rob Gore says “are all about yield.”

Deeper into Somerset, Yeo Valley settled on something more towards the middle ground – their British Friesians, originally a Dutch variety now bred in the UK to be a bit more robust, “average around 600 kg and are bred specifically for grazing,” Yeo Valley’s Farm Development Manager Will Mayor tells the WFJ. “Compare that to the weight of a high-producing cow that is housed, and this could be around a 750 kg animal.” Palette & Pasture is another Somerset ice cream maker (though they prefer ‘gelato’) who eschewed the black and white Holstein Friesians synonymous with dairy farming for smaller, less intensive cattle – in their rare case, bringing back the Somerset Sheeted virtually from extinction.

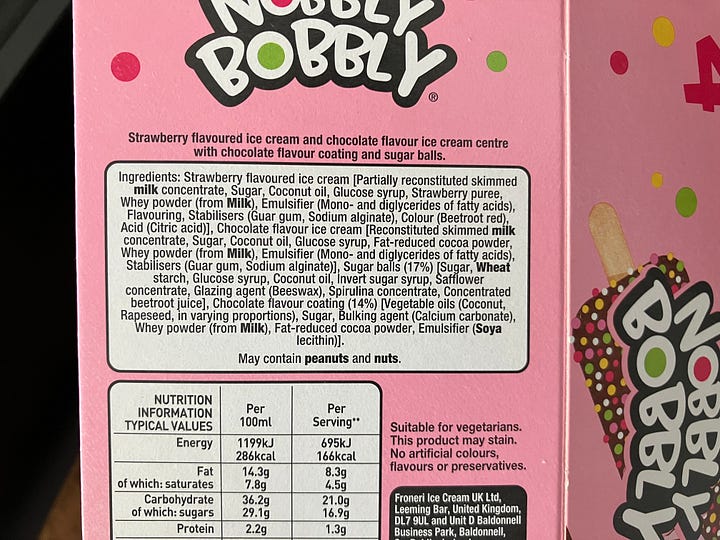

Local makers of ice cream are also tending to win out on the wholefoods battle. Recent backlash against ultra-processed food and its effects on public health has meant more people are turning their attention to the ingredient lists on their favourite foods. Should they glance at some of the UK’s top-selling ice creams, they won’t find much relief – a Magnum Classic, for example, consists of reconstituted skimmed milk, sugar, water, cocoa butter, cocoa mass, coconut fat, glucose syrup, glucose-fructose syrup, whole milk powder, whey solids, butter fat, and various emulsifiers, flavourings, and stabilisers.

“There are too many ways to make ice cream cheaper and easier, which is all too tempting,” says Rob. “We make all our flavours from scratch, starting with the raw ingredients.” This entails roasting strawberries in their kitchen, growing mint in their garden, and souring from like-minded producers such as Blackbee Honey, Landrace, and Pump Street to supply Brickell’s honeycomb, cinnamon toast, and chocolate flavours respectively.

It’s a similar story for Yeo Valley, relying on organic double cream (albeit some of which in powdered form), sugar, vanilla, and egg yolks. The benefits of producing and processing all of this organically is well-documented and easy to understand from a consumer perspective, though Rob suggests it’s not necessarily the silver bullet some producers are looking for. “Certainly at a supermarket level, some of the organic ingredients we would question their country of origin,” he says. “Then you're getting into a debate of whether environmentally it’s better to buy from a farm down the road or ship it in from another country for an affordable organic certification. We don't for example have an organic egg yolk supplier locally that can supply the quantities we need.”

You might’ve got this far wondering if any of this really matters, and at one point I did too – ice cream is, after all, a luxury we can ignore if we wanted to. But having had my first Brickell’s of the season (the chocolate in particular is something to behold), it’s reminded me that when a food like this is more environmentally sound, holds welfare to a higher standard, and – ironically – doesn’t rely on flavour enhancers, additives, and other whatnots, that usually vastly improves how it tastes too.

Hepling bring about Somerset’s ice cream counterculture are, among others:

Brickell’s

‘Flavour first’ ice cream using milk from Westcombe dairy. Ordered direct or found in various shops such as White Row Farm Shop, Higher Farm, Teals, and Trading Post Farm Shop.

Yeo Valley

Somerset’s only organic-certified ice cream. Generally found in ASDA and Waitrose stores.

Swoon

Gelato (that’s to say, less fat content than your usual ice cream) made from Bruton Dairy milk. Parlours in Bath and Bristol.

Palette & Pasture

Trudoxhill gelateria using milk from their ten ‘ice cream cows’ in Trudoxhill. The herd has transitioned from 200 Holstein Friesians down to ten Somerset Sheeted.

Styles Farmhouse

Traditional ice cream makers, with their own fleet of solar-powered vans, based near Minehead. Milk from their Jersey herd on Exmoor.

Hoolee’s

Various takes on the ice cream sandwich. Sells out of The Frome Independent and Owen’s Sausages and Hams.

👏

Excellent piece