Can independent shops beat supermarkets on price?

While in Frome on a weekly food shop, I wonder: are independent retailers really as expensive as people think?

I always thought the main (or rather, the only) way supermarkets beat local independent food shops was on price. That’s the line they all lead with, after all — “That’s Asda price”, “Lidl on price”, “Live well for less”, and so on.

It so turns out that that’s not always the case. Or when it is, the differences aren’t as significant as we all might think.

The last time I compared food prices across bricks-and-mortar retailers was about two and a half years ago.1 And so, last week I wondered: how much have things changed since then? Am I now getting fleeced at local shops, or do they still represent a fair deal?

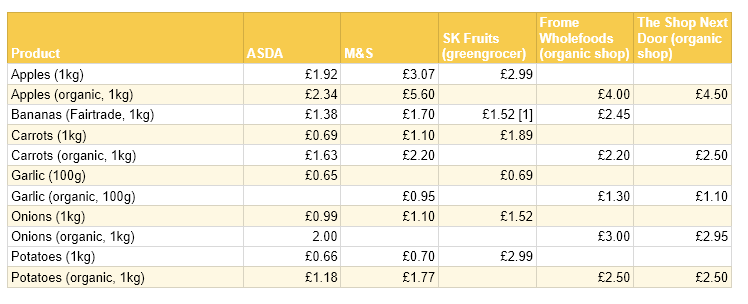

To figure that out, I went into my local town (Frome) to record and compare the prices of 48 items (aiming for what most would consider a weekly staple) across seven retailers, including the local branches of Asda and M&S.

Feel free to peruse what at the time felt like (but definitely isn’t) an exhaustive list,2 from smoked streaky bacon to organic white basmati rice. Similar results may be or may not be found in your local area.

How do prices at independent food shops compare with those at ASDA and M&S? Find out from the list here 👇👇👇

Obviously you’re free to draw your own conclusions from this, though I’ll lend some more detail below. If there’s only one takeaway you’d like to leave with, know this: conveneince comes at a cost. Whether it’s bringing your own refillable packaging out with you, or butchering a chicken yourself, sizeable savings could be made if we shopped for food a bit differently.

And yes, if you’re happy to take the time to shop around, patronising supermarkets is by no means always the best way to save money.

Highlights:

Fruit & veg

In short, if you’re buying organic fruit and veg from the supermarket (especially M&S), you might get a similar deal — or even save money — at your local independent grocers.

Not sure why those shopping at SK Fruits are paying sometimes 50% more than at other shops, mind.

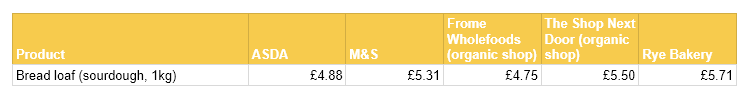

Bread

This one comes with the huge caveat that not all sourdough (for the sake of comparison with independent shops, the only bread item I thought worth listing here) is really sourdough.

The jury is still very much out as to whether loaves marketed as ‘sourdough’ sold in supermarkets are consistent with the Real Bread Campaign’s definition (naturally leavened, containing little more than flour and water), as supermarkets continue to get themselves into hot water in misleading shoppers as to what their bread actually contains.

The prices below kind of reinforce that – despite cutting corners in an attempt to produce and/or sell a cheaper loaf, large retailers are still struggling to provide much value when compared to artisinal bakeries and independent retailers.

For those interested, the organic shop loaves listed were from Hobbs House Bakery.

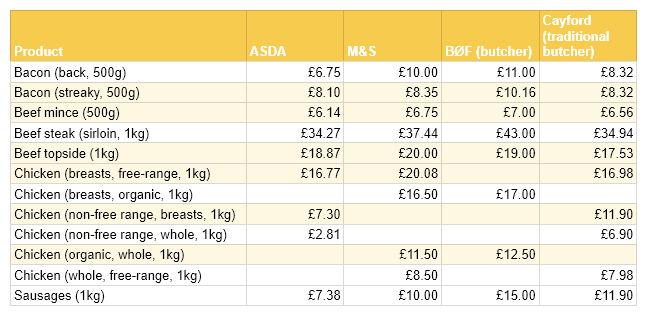

Meat

Probably the trickiest category to compare prices on, mostly for the lack of transparency from larger retailers in how their meat is produced (e.g. welfare and environmental standards), but also the variable nature of meat quality. Do you always get better meat from a butcher? No, but some you can trust more than others, and often transpire — as you’ll see below — to be more reasonable than larger retailers.

There’s also a fair amount of ‘hidden value’ in butchers’ shops — they can tell you exactly what farm the cow they have in is from, perhaps even its breed, and how that influences the flavour. Ask a sales assistant in M&S how long they hang their meat for and they’ll no doubt give you an incredulous look.

Something else to consider here is the price of butchery. If you’re in Asda and two chicken breasts weigh about 440g from a 1.7kg bird, the breasts from that bird will equate to about £1.36. If you were to buy the same breasts separately, they will cost you £3.49.

Similar markups are true of butchers’ shops and the main reason why I almost never by any chicken but a whole chicken — as god intended — and have learned in both senses of the word to butcher said chicken (which is genuinely quite straightforward) at home.

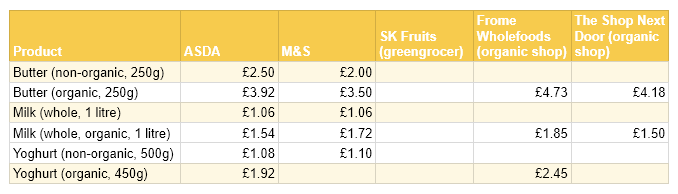

Dairy

Butter and yoghurt prices have not fared well over the last five years. I remember all too fondly when a block of organic butter from my local independent food shop was £2.50. Now it’s almost twice that, with some brands (I see you, Yeo Valley), ‘shrinkflating’ their products by 50g to make the cost more manageable for shoppers.

Nevertheless, prices for organic milk are pretty competitive across all retailers, and in this town at least it seems the best deal (Ivy House organic whole milk) is offered by an indie shop – albeit with the help of the one litre bottle you’ve remembered to bring along with you.

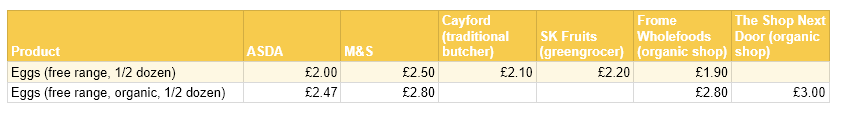

Eggs

Whatever the status of your chosen retailer, the price of eggs is pretty similar across the board. You may even save a few pennies at your local independents.

Though I didn’t record thier prices here, note butchers’ shops tend to be a reliable source of affordable eggs too.

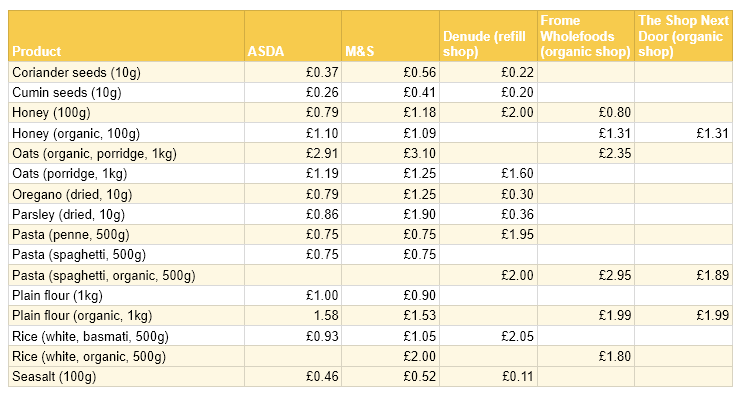

Sundries

Refill shops are low-key beating supermarkets on price in a number of areas. First and foremost, dried spices. This says a lot about the cost of packaging (both in financial and environmental terms, it must be said), but the fact your local refill shop might sell you items at half the price of your nearest supermarket sans jar, bottle, or packet is something that curiously flies under the radar.

General notes & observations:

Prices were true at the time of writing this (mid-October, 2025).

Mentioning anything to do with ‘food prices’ is a great way to send the British public into turmoil. Mainstream newspapers clearly know this — of late, you’d think we’d undergone a national crisis over the cost of food, though simply comparing the labels of the same foods over two and a half years, the dial has barely moved. Sausages, eggs, bacon, butter, and spices for example have barely gone up in price, if at all. I should say that more anecdotally than anything else.

Organic and organic-equivalent products may be more expensive, but what of their value? More research has come out in the last few years suggesting that, at least from a nutritional perspective, some organic food offers more bang for your buck.

That being said, while the organic label is the best way to quickly determine the environmental and possibly nutritional credentials of a particular product, it usually comes with a heftier price tag (for the farmer and consumer) and is not necessarily ‘better’ overall than buying from small local producers you trust. I go into more detail on that here.

Prices give us a big clue about how something is produced. Asda’s cheapest chicken for example, at £2.81 per kilo, certainly means it’s well within the majority of how chickens are farmed in the UK – hundreds of thousands of them crammed in massive sheds, grown fast and with high rates of lameness, and no access to the outdoors. Meanwhile, BOF’s chicken (albeit four times the price of Asda’s) is at the time of writing from Stream Farm, an organic and regenerative farm in the Somerset Quantocks who rear their chooks on pasture and at their own pace. They taste a heck of a lot better too.

Similar goes for things like honey and bread, though these are more about what’s real and what’s not – pick up a jar or bottle of ‘honey’ from a supermarket shelf and chances are it’s not in fact honey but mostly sugar syrup. Since honey is not legally defined, this is not considered as fraudulent a practice as it should be.

If not all foods are made the same, is it fair to compare them at all? There’s a strong argument for claiming that, I think.

Understanding why food items cost what they do is a rather a nuanced and complex a thing and something I’ve often tried to unpack – see for example what goes into a £10 bacon sandwich.

Independent shops are much more likely to stock local products. And ‘local’ doesn’t mean ‘more expensive’ — milk (Ivy House and Bruton Dairy in Somerset), honey (Wainwrights in Wiltshire), beef (Blue Carbon Farming in Somerset), and chicken (Creedy Carver in Devon) are some products that are similarly priced regardless of where they’re from or whether they’re stocked in a supermarket.

Let us not forget the importance of what we spend in contributing to local economy. As The New Economics Foundation found, every £10 spent in a local food business is worth £25 to the local economy, which further improves local ameneties and services. When you spend that money at a supermarket, much higher is the chance it ends up lining some CEO’s account in the Canary Islands.

Any other money-savers you’ve noticed on your weekly shop? Let us know in the comments.

Paid subs will also know a) how much I tend to spend on food on a monthly basis, and b) where exactly I spend it — in short: a) less than the average Brit but b) mostly at markets, organic shops, and other independent stores. Though these numbers are two years out of date, they are still roughly accurate now.

Sometimes finding exact comparisons was tricky (e.g. varying leanness of beef mince, or inconsistent varieties of potatoes), so prices of supermarket items displayed are those that are close as I thought appropriate to their independent equivalent.

Supermarkets don’t do a by-weight on items like fruit or veg, so I had to work out the average weight of an onion or an apple (quite variable, obviously) in order to be able to compare the price.

A lot of the items in supermarkets are clearly sold as loss-leaders, meaning their price doesn’t reflect their actual cost. But then this is often true of products in supermarkets in general.

For the sake of fair comparison, this whole excersise focuses on ‘traditional’ retail. Other forms of doing one’s shopping, such as online or at the farmers’ market, may be more cost-effective (fewer rent and overheads will help with that), howevermuch at the cost of convenience.

Hugh, we need to talk about chicken!

Meat chickens are not beak trimmed and natural daylight is part of the Red Tractor scheme, which encompasses the vast majority of chicken produced in the country for retail.

I also think some clarity is needed around producers like Creedy Carver. I've seen these birds and they are fast growing broiler genetics reared in a free range environment. It's an ethical fudge.

The irony is some of the major retailers are a lot more transparent when it comes to their production methods, the smaller guys go under the radar and can do what they like.

The Guardian taste reviewed various chicken producers last weekend, complete tosh.

We probably should discuss over a pint!

Honey is defined in Law in the Honey (England) Regulations 2015. This section defines what it should be:

2.—(1) In these Regulations “honey” means the natural sweet substance produced by Apis mellifera bees from the nectar of plants or from secretions of living parts of plants or excretions of plant-sucking insects on the living parts of plants which the bees collect, transform by combining with specific substances of their own, deposit, dehydrate, store and leave in honeycombs to ripen and mature.

----

The issue is that the big honey packers aren't keen on their products being looked at too closely.

I am a beekeeper, if you want genuine honey then avoid any "honey" on the shelves that says "A mixture of honeys from EU and non-EU Countries."

Buy directly from a local beekeeper or a shop that gets their honey from a local beekeeper. If you shop in M&S then any honey from Wainwright's Honey will be good. They are based in Wales and produce some good honey. They also, IIRC, import honey from Kenya which is of good quality.

HTH.