Somerset's most fertile lands could be lost forever

On the Somerset Levels, humanity might be about to lose its ancient battle with nature

Somewhere around 1770, a Burnham farmer by the name of Richard Locke rallied local landowners – and some of their tenants – to ‘reclaim’ (specifically, improve the drainage of) the large, flat, but flood-prone region first known as the ‘summerlands’ and later known as the ‘Somerset Levels’.

His motivation? With rapidly-industrialising Britain undergoing a population explosion (well on its way to almost doubling by 1850), the country needed a better way to feed itself. And more land with which to do it.

This wasn’t the first time such an endeavour had occurred on the Somerset Levels. By Locke’s time, those inhabiting the region – now amounting to 250 square miles sandwiched between the Mendip Hills and the Quantock Hills – had drained or otherwise exploited it, in piecemeal fashion, for thousands of years. This included the Romans, partially attracted to the area to extract salt, and neolithic peoples who, 5,800 years ago, left behind what was later unearthed as the earliest evidence of dairy farming in Britain.

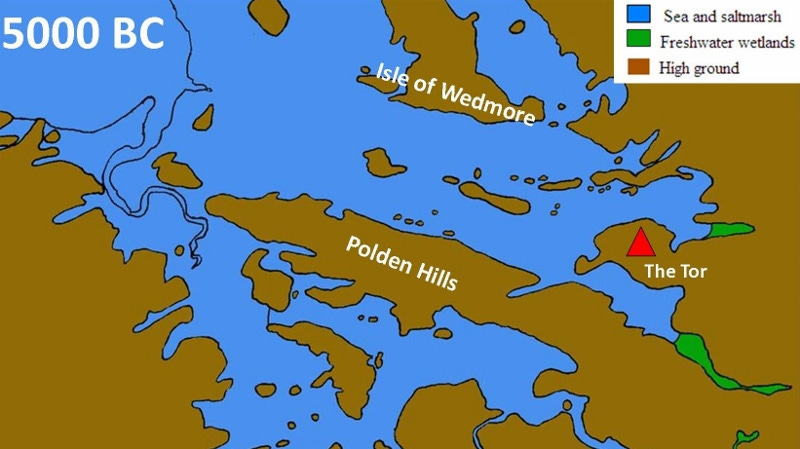

Back then, early in human history, most of the Somerset Levels and Moors were underwater. The rest of it formed an archipelago, with islands the Saxons named such as Chedzoy, Muchelney (meaning, ‘Great Island’), Godney, Thorney, Athelney, Middlezoy, and – even as we know it now – The Isle of Wedmore.

Of course, these places still exist. They just look quite a bit different (see also Glastonbury Tor, perhaps most famously). For better or worse, gradually improving technologies in embankments, sea walls, ditches, dredging, and pumps, ensured the land could, and would, produce.

Bit by bit, and most notably from the medieval period onwards, these ‘improvements’ drained more and more water into the Bristol Channel, leaving richly fertile land behind – land that would be used for growing crops, or more commonly, grazing cows and sheep on plentiful grass.

Drainage efforts on the Somerset Levels and Moors, as they became known, also decreased the risk of flooding, which led to more settlements and more agriculture. This didn't mean the area was immune entirely, as the floods of 1607 and 1872 in particular (subsuming 200 and 107 square miles of farmland respectively, not to mention taking quite a few lives on the way) served as a reminder.

In more recent memory are the floods of 2014, which engulfed 165 homes and 25 square miles of otherwise dry land. Many local farmers still shiver at the thought. Now, almost exactly ten years down the line, record-breaking levels of rainfall have left Somerset farmers in a similar kind of stress – in a recent BBC interview, dairyman Alan Franks, who’s farmed on the Levels since the 1950s, said the floods in March were “the worst I’ve ever seen”.

At their peak, 350 acres of Franks’ land was rendered temporarily unproductive. Other farmers in the country were or still are facing the same thing, with some warning the country that the autumn, winter, and early spring wet weather will undoubtedly reduce domestic harvests. Already, there’s been a 15%, 28%, and 22% reduction in wheat, oilseed rape, and winter barley respectively.

Franks says the Somerset Levels will probably be unfarmable in the future. A statement less surprising when given the history of the area – human civilization has always fought an uphill battle maintaining an artificial landscape against nature and its proclivities, and will only find it more difficult if extreme weather events increase in frequency (as they are expected to), and as sea levels rise to a critical point. It might sound an estimate of the extreme, but Climate Central suggests most of the Levels will be underwater within the next six years.

Even without these relatively new threats to its existence, farming on the Levels is not exactly a financially resilient endeavour – the Environment Agency, Somerset Council, and Somerset Rivers Authority already spend hundreds of millions of pounds in dredging, pumping, and other maintenance of the Levels (before accounting for the hundreds of millions in flood damage).

It might be that they didn’t have the choice. But I wonder, if Locke and those after him had known the ultimate costs – both financial and otherwise – of bending these large parts of Somerset to their will, whether in the long term they’d still think it was all worth it.

Beautiful Photograph. Poignant tale.

Hindsight is a wonderful thing!