One year of The WFJ [WFJ #52]

Some candid reflections on food and farming in Frome, and the process of documenting it

When I moved to Frome, there wasn’t a publication obsessively honing in on food and drink in the area.

So, a year ago, I created it.

52 weeks and 52 issues later, I feel like The WFJ is still establishing itself as something that helps the local community make more informed decisions around what they eat and drink.

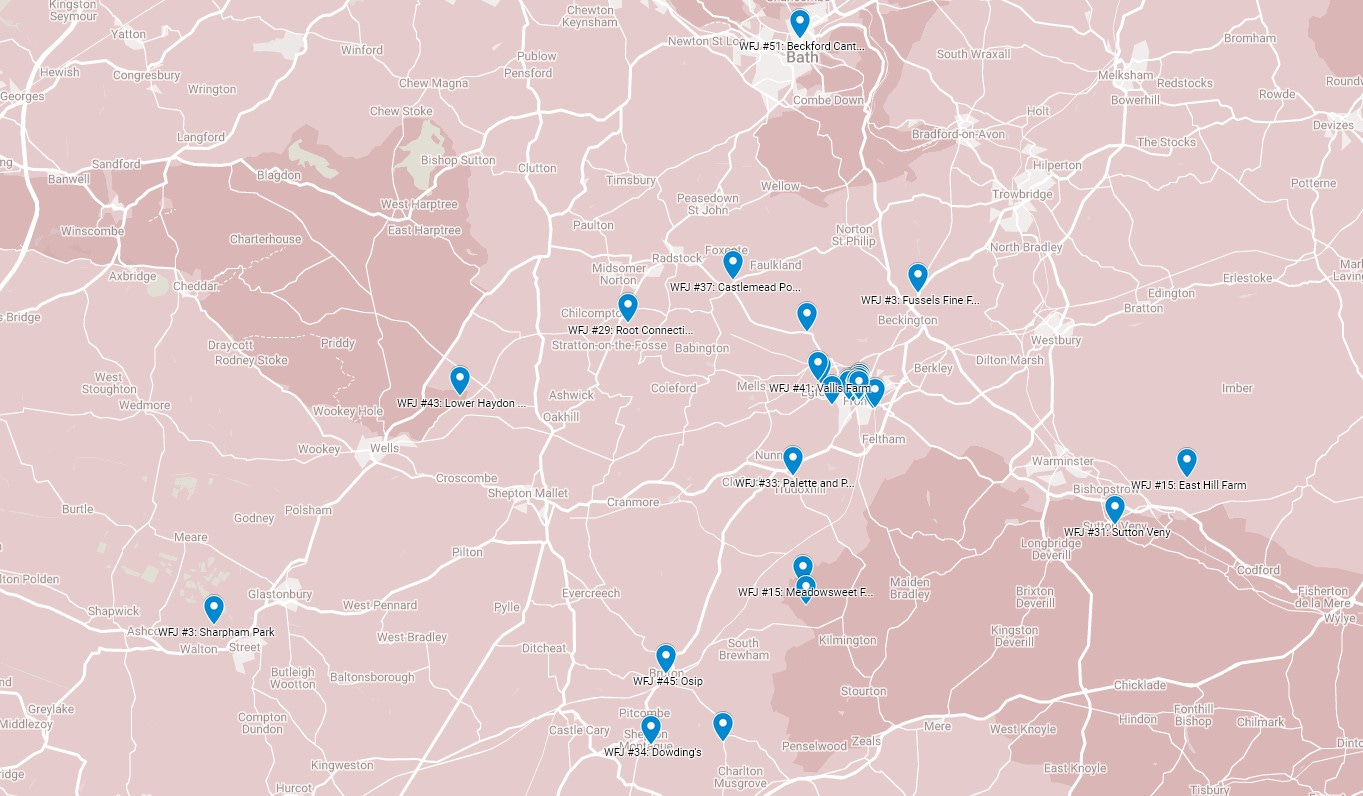

In the meantime though, it’s also painting a picture of Frome’s food landscape – what we as locals can celebrate together or boast about to those not living in the area, as much as understanding the issues Frome (and often by extension, the rest of the UK) faces from a food and farming perspective.

There are plenty of nuances, but based on the last 12 months we can characterise Frome as such: It is conscious of its pollinators, like bees. It has farms farming ecologically who – either brave or insane – want to serve the Frome market exclusively. It’s beginning to proactively explore what food sovereignty means. It hates food waste. It has its own version of the negroni. It’s home to a collective of local businesses and food-curious individuals seeking to make the food environment more accessible, sustainable, and dynamic. It does a variety of mince pies.

Ultimately, the range and quality of food businesses best demonstrate how Frome has become such a unique Food Town. Some of its issues relating to food, however, often show it’s just like any other in the UK: Its chippies are on life support; 99% of what its locals eat is controlled by supermarkets; it’s got factory farms – some of which are the most environmentally and ethically questionable in the country – on its doorstep; its local food infrastructure is fragile at best; its surrounding villages are contending with rural decline; and it has social, economic, or skill-based barriers between farm and fork.

Though often unpalatable, these are the kinds of stories that need telling. I guess this is why you’re here too, but rather than what food media usually feeds us, I want to read something closer to reality. Something which charts the lows as well as the highs while uncovering the stories otherwise left untold.

Which reminds me – if The WFJ’s investigations, celebrations, and documentations have made your life even a teeny bit better, do consider subscribing.

12 lessons learned from 12 months of The WFJ

If you want to produce food round here, it’s much more likely to work if it comes with some sort of broader impact. Whether environmental, social, or what have you, the best products are often byproducts of a benign scheme.

Recording and investigating food-related stories in a small town – not necessarily in a way lots of people will pay for it – is actually slightly mad.

Hyperlocal journalism has its pros and cons, such as a relatively small audience, but pretty decent engagement. Accordingly, I’m usually ignoring PRs’ requests to feature the chefs they represent in a national newspaper. These days, they’re ignoring my requests to interview their chefs for my tiny publication.

Everyone’s a ‘foodie’, but very few people like to think more in depth about food. I used to post WFJ articles regularly on the Frome Facebook page, which received relatively little interest out of the 30k members.

‘Foodie’, I think, should be redefined as someone ‘interested in food insomuch as the basic pleasure of putting it in one’s mouth and, occasionally, assembling ingredients exclusively according to predefined instructions’.

Either arrogantly or naively, when I started I didn’t think I'd need to promote The Wallfish all that much. I also refused to believe leafleting was relevant in the online age. Yet here I am, printing flyers to distribute around town.

“Oh you’re the one who writes that food blog”. At some point I may have to swallow some pride and come to terms with being a ‘blogger’. It rouses certain connotations, and as I’m more used to being called a food journalist, does it mean I’ve been demoted?

When I started The WFJ, I would tell people it was an ‘experiment’ to see if locals actually wanted something like this. What I said was partly true, but also partly a coping mechanism to explain why takeup was – to me – surprisingly slow. As for whether the ‘experiment’ was a success, hopefully the fact I’ve partially monetised it since November will help answer that.

Also when I started The WFJ, I had in mind to write content for people ‘concerned about the industrial food complex’, and ‘wanted to change their relationship with it’. While much of that still stands, the publication’s best-performing articles are to do with festivals, pop-ups, and other events…

Curiously, some people who don’t live anywhere near Frome are still happy to pay for what The WFJ publishes.

A few people asked me to write something on how to buy good, local food cheaply. I tried drafting something a couple times, but it felt like stroking a cat backwards – local, responsibly-produced food is ‘expensive’ in the same way cheap food is cheap. One is often (but not always) produced slower, with things like animal welfare and nature in mind, while the other has significant environmental costs hidden from the consumer.

As an addendum to the above, good local food usually doesn’t cost as much as it should. When labour, inputs, rent, and every other expense to the producer is accounted for, the margins on a sale of, say, a bunch of carrots is prohibitively small.

What’s next

If those learnings help explain where we’re at, then where are we going?

For starters, I want to visit, and document, every pub in Frome; better understand 42 Acres’ supposed transition to a more community-driven mindset; explore what the Frome bobbin says about regionality; relate the story around local community growing initiatives; report from the frontlines of Frome’s war on food waste; understand why a bacon sarnie in Rye bakery costs £8; visit at least one of Frome’s traditional caffs (not cafes); and revisit July as Frome’s ‘food month’.

But I also want to hear from you – what do you want me to investigate? What questions around food and farming in the area would you like answering? Why did you even subscribe!? The comments section awaits.

A WFJ highlight reel, of sorts

Consider the following a reminder of – or an introduction to – the kind of topics The WFJ touches on. Some of which are from articles paid receivers get, while others are from free-to-read editions.

Delivery platforms as a necessary evil, from Deliver-oh no:

The issue might not be so much these delivery apps as the demands that are, increasingly, making them relevant. “We know there's people who do not want to go out, which I personally think is mad,” says Dom. “If I'm in a tiny town which takes five minutes to get anywhere, I'll go get it. But people don't. Some people would rather order in and get worse food than go out and get better food. For me that's not a concept I understand, but it's definitely the case.”

The cost of cheap bread, from Why a locally-made sourdough loaf costs £4.50:

Come forth the Chorleywood process, a breadmaking method that emerged in the 1960s. With the help of various chemicals and processing aids, including a crap ton of fast-acting yeasts, industrial bakers are able to make bread from flour to packaged loaf in three to four hours. It made bread 40% softer, and gave it a shelf life twice as long as before. The trade-off? Your gut might not be too much of a fan. Perhaps it’s just a coincidence, but celiac disease – the gluten-induced digestive and immune disorder – has been ever-rising since the mid-21st century.

Untangling nuances in the food miles issue, from What does buying local food do for the environment?:

Critics of buying and eating from small, local farms – i.e. those who think we’ll starve unless we submit to the industrial food complex – say that bigger, centralised farms are more efficient, and are therefore more reliable, in feeding populations far and wide. That might technically be true, but such approaches inevitably result in intensively farmed soils, nutritionally deficient crops, and severe biodiversity loss.

When someone talks of ‘efficient’ farming, usually they’re talking about achieving food production as quickly as possible through the use of agrochemicals, lower animal welfare (antibiotics, overstocked land), and monocropping. Ironically, this necessitates alternative practices among smaller farms to help overcome the environmental issues the industrial ones have caused.

The role of ruminants in regenerating the local landscape, from Saving the planet… with cows?:

When managed in a certain way, cattle can help store carbon in the soil under them, facilitate biodiversity, and (by no coincidence) provide some of the best-tasting meat at the end of it.

On East Hill Farm, some 12 miles from Frome on Salisbury Plain, Frankie Guy’s 300 cows are involved in a conservation programme to promote diversity on the grassland. “On the conservation areas, you don't want the grass to grow too much,” she says. “So if you go in in the spring and graze it down really hard, it gets rid of the competitive grass and helps the more delicate species that take longer to come through.”

How bees prop up the ecosystems upon which humans rely, from Without bees, we all go hungry:

Bees pollinate food eaten by other animals and birds, and are key in meat and fish production – losing them would have a domino effect on the food chain because cattle, chicken and fish are all fed on plant products highly reliant on bee pollination. They contribute greatly to the enrichment of our landscapes – the green spaces we rely upon to bolster our mental health would look very different without regular apian attention.

Establishing Frome’s heirloom vegetables, from Sowing the seeds of food sovereignty:

Another part of the project is focussed on amassing a collection of heritage and heirloom seed that has, over time, naturally adapted to thrive in the local climate, soil, and environment. Thereby offering an alternative to purchasing new seed – that’s bred in and adapted to who knows where – from a gardening centre each season. “It will make for a better crop that in the long run will be more resilient,” says Kerry.

“So hopefully, in ten years' time, we can have the lineage of Gordon's Runner Bean. And that may very well happen, because Gordon has donated from the Frome Selwood Horticultural Society,” Kerry says. “We know – because he's been growing it for however many years – that it loves Frome soil and that it's a good cropper.”

Mapping out the local farms poor on animal welfare, from The rise of the mega farm:

The farms fitting within this intensive category of ‘agriculture’ – that is to say, those with at least 40,000 birds – include Beard Hill Farm outside Shepton Mallet, Woodborough Farm near Bath, and Oakstone Farm the other side of Westbury. Transparent Farms UK maps these intensive poultry and other livestock units, like Clapton Lane Piggery near Radstock, where more than 2,000 pigs are housed. The farm is run by Crockway Farms, which has been linked to instances of pigs kept in ‘appalling’ conditions with little to no access to natural light. This particular farm was approved by Red Tractor – the label that, in its own words, indicates food products “traceable, safe, and farmed with care.”

The somewhat environmentally-friendly evolution of Palette & Pasture, from 'It’s not the cow, it’s the how':

In the 1930s, Somerset Sheeteds – Somerset’s most ‘native’ breed – became virtually extinct in the UK, most likely due to a rapidly industrialising agriculture system that needed to feed a rapidly growing population. Paul puts it into context: “the Holsteins were making around 10,000 litres of milk per annum. The Somerset Sheeteds are going to be about 3,500 litres.”

How the farming sector can – and is – attracting the next generation, from Vallis Veg is empowering young growers:

As Britain is under pressure to encourage a new generation of food producers to relieve its preceding ones, it finds itself attempting to rally a cohort of people too ‘lazy’ to work on a farm. That’s one theory anyway. In another, and as recently discovered by The Landworkers Alliance (LWA), young people do want to get into agriculture. They just don’t want to get into conventional agriculture, with all the synthetic fertiliser, wildlife depletion, fossil fuel dependence, and other environmentally-unfriendly measures it entails.

Osip’s Merlin Labron-Johnson on the meaning of sustainability, from Under the hood of the UK's 'best restaurant':

All this is to say you could call Osip, if you wanted, a ‘sustainable restaurant’. It is, however, a term Merlin despises, and for good reason. While in London, working towards his vision of a ‘sustainable restaurant’, he noticed other restaurateurs trying to do the same. Some, though, were more vocal about it than they were proactive. “I saw through a lot of bullshit,” says Merlin. “And found it frustrating and became disenchanted with the whole public appropriation of sustainability.

Really value your writing Hugh and this candid and funny and insightful 52 weeks of Wallfish. I wouldn't normally subscribe to a 'foodie' online mag, but I really enjoy the way you make me think about food and sources of food in all kinds of ways. Thank you!