One bean, an ecological crisis, and a 5,000-mile headache

Are we helplessly complicit in farming's destruction of the world’s most precious ecosystems the other side of the world?

A couple of months from now, various leaders of the world will assemble in Brazil at COP30, the UN conference on climate change. To get there, they’ll be chauffeured from Belém airport through eight miles of rainforest flattened just in time to make way for a new four-lane highway.

The irony – indicative of governments’ general impotence in addressing climate change and biodiversity loss – seems to have triggered everyone but those taking part. Of course, eight miles of rainforest is relatively nothing – whether the Amazon basin, Somerset Levels, or virtually anywhere else in the world, the main perpetrator of deforestation, and subsequent effects on ecosystems, is agriculture. 300,000 square miles of Amazon rainforest have been cleared in the last 50 years, primarily for the cultivation of cattle, but also crops like soy bean.

The issue of erasing parts of one of the planet's most important carbon sinks to ranch cattle is well-documented, and (ostensibly) straightforward enough for you or I to respond to – if we buy meat from livestock raised on UK pastures, then we aren’t directly supporting a part of the industry as destructive. Soy bean, however, is a lot harder to avoid, as a kind of pivotal – though usually invisible – staple in the global food chain, present in 60% of manufactured foods. 5,000 miles away in Somerset, that pint of cow’s milk you have in the fridge, that cake you picked up from the supermarket, or that bacon you bought from the butcher, has more than likely relied on the clearance of rainforest (legally or otherwise) for soya.

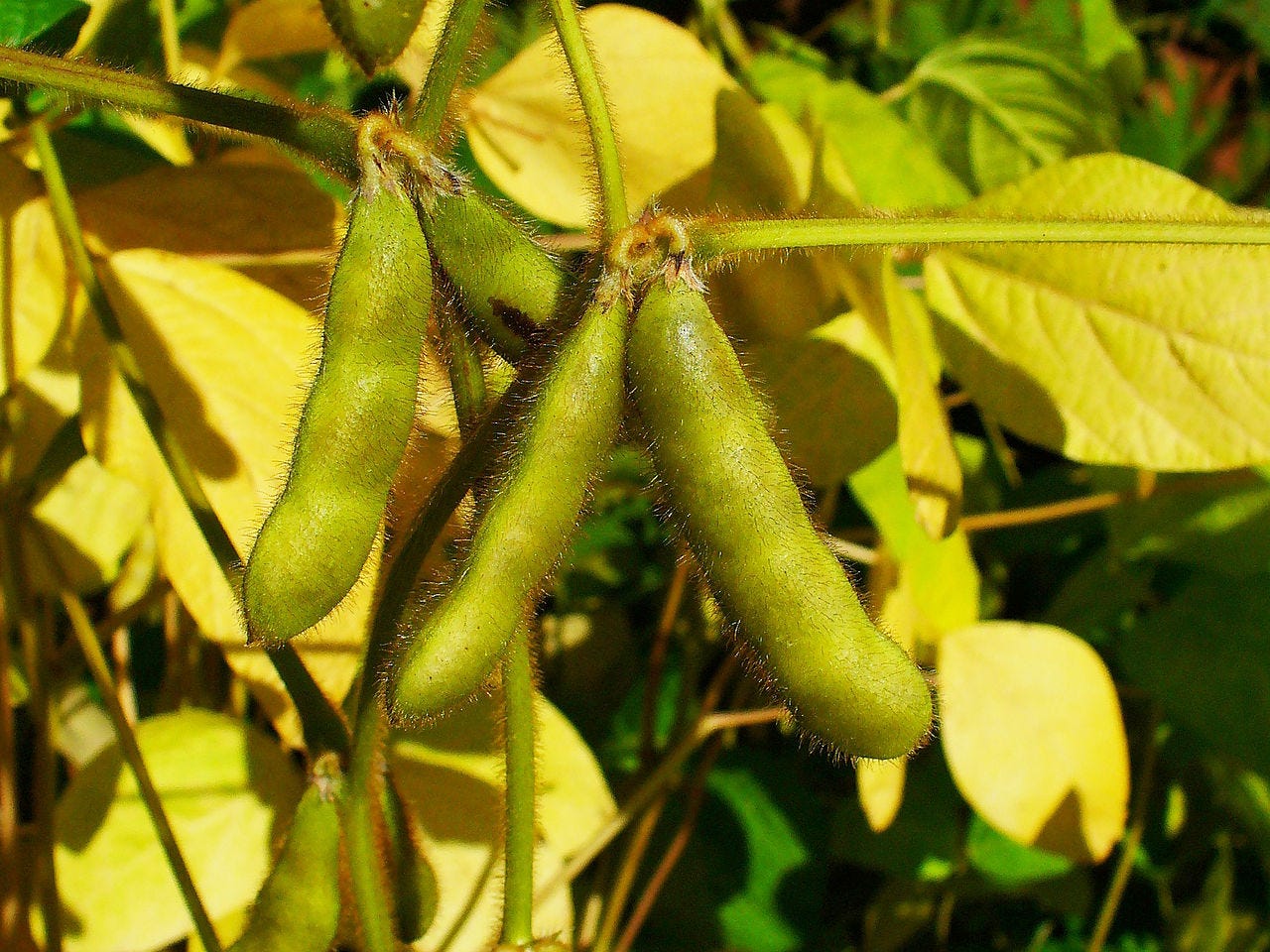

350 million tonnes of soya bean is grown around the world (for reference, not far off the global yield of potatoes, at 375 million), almost half of which in South America. Though it’s used in everything from soy sauce, tofu, and miso to salmon food, meat substitutes, and protein powders, 75% of all soya grown ultimately forms the main protein element in livestock feed. “Soya bean is very digestible to animals, and the amino acids in it are really important for pig and chicken growth,” farmer Amy Chapple tells me. “That’s why it’s so widely used.”

Amy, who farms in Tiverton and also over the border in Somerset, produces beef, chicken, lamb, and pork as part of a regenerative system. She’s made a point of not feeding her animals soy, partly because of the environmental ramifications usually bundled with it. Like Amy, chief exec of the Soil Association Helen Browning farms pigs in a manner more responsible than the vast majority of those in the UK (95% of swine in the UK are factory farmed). “Soya is not a ‘bad’ crop,” Helen says. “It’s about where and how it’s grown that can be problematic. We think of soy as associated with deforestation, or with very intensive GM methods, but that needn’t be the case, and of course, as an organic farm, we must use organic soya if we are going to use it at all.”

Even so, “When the supply chain is so long and it's coming from so far away, you can't really put 100% trust in it,” Amy says. In her case, this even extends to organic soya, which Amy has heard rumors of “more landing in the UK than what leaves Brazil,” suggesting some soya magically becomes organic as it crosses the Atlantic. This concern – by no means exclusive to Amy – has caused her to source everything she feeds her pigs and chickens from the UK. “And most of it within 15 miles of me,” she says. This means diverting from soya entirely – it being native to East Asia, significant soya yields in the UK are a rather far-fetched prospect at the moment.

If it is true ‘deforestation-free’ soy is mixed with soy grown in deforested areas – and it seems bordering on impossible to prove if it is or not – then the various commitments towards more responsibly-sourced soy made by the likes of McDonald’s, Ocado, Nando’s, Gregg’s, and Sainsbury’s, are a tad hollow. And that the UK Soy Manifesto, a cross-industry initiative to ‘ensure all physical shipments of soy to the UK are deforestation and conversion free’ by the end of this year, could be worth less than the paper it’s written on.

But before we make such sensational and not exactly watertight statements, there are others a little more substantiated to consider. Like for example, the continuing neo-colonialist practice of seizing indigenous people’s land to grow and sell soy bean for the global market; or that some Big Food companies might be honouring their pledge to not contribute to the destruction of the Amazon, but regard other South American rainforests, like the Gran Chaco, as fair game.

At this point, you might be thinking: Can we not simply renounce the practice of sourcing far-flung foods produced under questionable ethics and in monoculture systems heavily reliant on agrochemicals (Brazil is a habitual user of pesticides classed as ‘seriously hazardous’ to humans, by the way), and over which we have little control? Well, at the ‘From Soya to Sustainability’ conference in Peterborough earlier this year, the numbers were crunched on exactly that. It was found that while it’s possible for the UK to cut its soya imports by as much as 50% to grow more domestic protein-rich fodder crops, this would probably result in a significant reduction in domestically-produced pork and chicken (an outcome you could argue needs to happen anyway).

The matter of fully trusting our food – or at least being comfortable with what sacrifices have been made in order to produce it – seems close to impossible when such a broad, global supply chain is involved. While localised food systems aren’t inherently more virtuous (though food produced in Britain is generally better for, say, animal welfare and low pesticide toxicity), they are much easier to trace. If the future of food is to be bright, then, it must start by being transparent.

Read next>

Somerset's (forgotten) fats

Olive oil – the UK’s favourite cooking oil – is in a bit of a crisis. Harvests in Spain, which produce half of the world’s crop, have fallen by 70-80% in recent times due to drought and rising temperatures, …